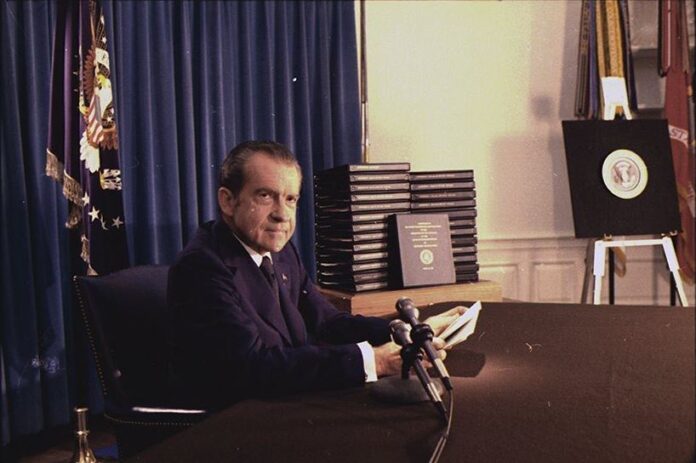

FEW WHO WERE ALIVE at the time could forget the Watergate scandal in 1972. The collapse of an impeached President was seen with frightening clarity. The whole ugly episode illustrated the point that the higher the office a man holds, the greater becomes his responsibility. Lesser individuals commit greater crimes with scarcely a mention when they are found out.

The fall of Moses, the great leader of the Exodus, was no Watergate. His character remained unstained. His faith, integrity, meekness and whole-hearted dedication to the welfare of his people would surely put all of our politicians to the bleakest shame. Yet in one momentary lapse he forfeited the prize of a lifetime. The story is not so well known, and it is worth retelling.

The people of Israel had wandered up and down the Sinai Peninsula for many years. The searing heat and the eye-aching whiteness of sand and scrub had become their life. Daily the heaven-sent manna was there to be collected on the open ground around the camp, and though gathering food, water and firewood took up much of the day, they managed well enough. That is, until the river dried up. The daily trek to the thin, life-giving stream that meandered endlessly across the desert was as automatic as getting up in the morning. Then, one day, the stream bed was dry. As the desert sun climbed up into the sky, panic broke out in the camp. An angry crowd assembled outside Moses’ tent, as if it were all his fault.

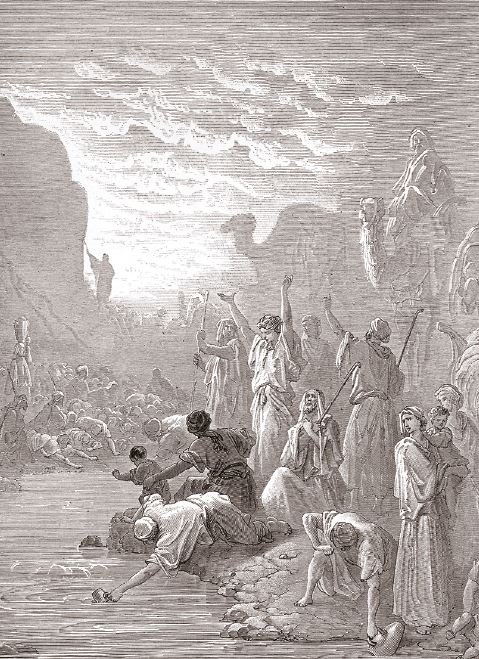

It was not the first time such an emergency had arisen. The community had run out of water before, many years ago when these men and women were children, on the other side of the wilderness (Exodus 17:1–7). That was now a dim memory, and their present need was pressing. Moses and Aaron, accused of bungling incompetence, sought help from the angel representative of God in the Tabernacle. Once more, the Lord saved the day. ‘Take the staff,’ he ordered, ‘and assemble the congregation, you and Aaron your brother, and tell the rock before their eyes to yield its water. So you shall bring water out of the rock for them and give drink to the congregation and their cattle’ (Numbers 20:8).

Rash Words

Moses took his trusty shepherd’s staff, and summoned the people together. When they were standing quietly, he raised his voice. There was anger in his tone, his patience with the people was wearing thin. ‘Hear now, you rebels,’ he shouted: ‘shall we bring water for you out of this rock?’ (v. 10). Lifting the rod high in the air, he crashed it down twice on the black cliff behind him. Immediately, a great plume of cold, clear liquid gushed out and ran across the sand in a growing flood. People and animals alike were soon gulping down the precious, life-saving water.

But God was angry. It was not the people who were in trouble this time. It was Moses. Time after time the people had blamed him when things went wrong, and this time he had had enough. ‘Shall we bring water for you?’ he had shouted. He never doubted that the water would come when he struck the rock. But God had asked him to speak to the rock. The way he put it, he and Aaron were the benefactors, while the Lord, the real source of the miracle, was left in the background.

It was out of character for Moses. David the Psalmist, meditating upon this incident years afterwards, said: ‘It went ill with Moses on their account, for they made his spirit bitter, and he spoke rashly with his lips’ (Psalm 106:32–33). However, God would not accept an excuse. ‘You rebelled against my word,’ he said to the contrite leader, ‘in the wilderness of Zin when the congregation quarrelled, failing to uphold me as holy at the waters before their eyes’ (Numbers 27:14). In putting himself before God, and producing the water his way, he had not preserved the high standard of respect that God demands. The Creator’s judgment was swift. ‘Because you did not believe in me, to uphold me as holy in the eyes of the people of Israel, therefore you shall not bring this assembly into the land that I have given them’ (Numbers 20:12). When he died, his bones would be buried outside the Land of Promise, like the others who had rebelled against God.

God Tests Us

This incident shows how a crisis searches us out. The Israelites depended on the river. Simply by allowing it to dry up, God put them under pressure. As Moses said to the people afterwards, He was ‘testing you to know what was in your heart, whether you would keep his commandments or not’ (Deuteronomy 8:2). He was searching Moses’ heart, too. Life is full of the unexpected. We must keep our thoughts unswervingly on God, listening to His word and doing precisely what He says. Then He will lift us up in His everlasting arms (Deuteronomy 33:27), and carry us through our troubles. And if we aspire to lead others, we must be especially on our guard against self- importance. ‘They that are low need fear no fall.’

Grumbling Again

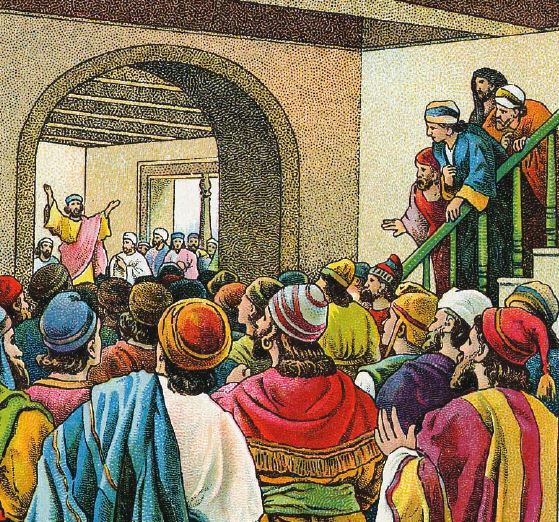

Another drama followed. The people had come to the frontier of the Edomites, south of the Dead Sea, on the last stage of their journey. The Edomites were related to the Israelites, being descended from Abraham (Genesis 36), but they refused them permission to cross their country. The Israelites had to make a long detour of 200 miles instead, ‘and the people became impatient on the way’ (Numbers 21:4).

A few grumbles escalated into a wholesale moan, and soon the camp was buzzing with complaints. ‘There is no food,’ they said, ‘and no water’ (v. 5), ignoring the fact that God continued to send them daily the water from the stream, and the plain but nutritious manna that was there every day. ‘We loathe this worthless food!’ they cried. They were tired of waiting for the Promised Land. It always seemed just round the corner. Once more they spoke against Moses. And soon they spoke against God.

Do you blame them? For most of the people, the wilderness had been their home all their lives. They had few luxuries —perhaps a little milk or cheese to eke out the manna and the water, and a day’s rest on the sabbath. Life was humdrum and hard. It is not surprising that their patience had expired, with nothing but promises to keep them going. Yet really, when you think about it, is not life just like that for many of us, most of the time? We pursue an uneventful routine from bed to table, maybe to work and back to bed, with only occasional breaks to relieve the monotony. And the coming of Christ, the great hope of the Christian, has been two thousand years in waiting, so that most believers have died without seeing it happen.

Do not Christ’s followers also live for promises? If they should begin to feel envious of their neighbours who seem to enjoy themselves without God, they need to remember that God faithfully provides them with homes and clothes and enough to eat, besides the promise of the Kingdom for the faithful (Matthew 25:21).

The great Apostle Paul languished in a weary prison cell, yet he could write: ‘I have learned in whatever situation I am to be content’ (Philippians 4:11). The Christian’s reward lies in the future, in God’s Kingdom. ‘I press on towards the goal for the prize’ was Paul’s motto (Philippians 3:14).

The Bronze Serpent

God was grieved by the Israelites’ lack of faith. ‘Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died’ (Numbers 21:6). Yet again, the magnanimous Moses went down on his knees to pray for the people. God showed him a remarkable cure for the venom of the snakes: ‘Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live’ (v. 8). It sounded an unlikely medicine. What difference could a bronze snake on a pole make to a dying person? Doubtless some Israelites stopped in their tents, moaning in pain, and refused to make the effort to crawl to the centre of the camp. The cure lay not in the serpent itself, but in the faith of the beholder. A lack of faith had inspired the grumbling that brought the fatal malady. Only rekindled faith in God would put it right.

Allegories

There is a rich and powerful allegory behind both of the events we have been considering. They lead us firmly to the presence of the Lord Jesus. The serpent in the wilderness is mentioned by Jesus himself: ‘As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness,’ he said, ‘so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life’ (John 3:14–15). The serpent is a symbol all through the Bible for human nature, our inward rebellion against God.

It condemns us all to die, like Adam our forefather, driven outside the gates of Paradise because he succumbed to the serpent’s lie (Genesis 3). Yet Jesus, the Son of Man, lived in a body just like ours, and never sinned. He choked back every selfish thought, through every minute of the day. That devotion to God’s will marked him out from his fellows. In Jesus, sin itself was put to death.

So when cruel men took this wonderful man and nailed him to the cross, and lifted him up in public view, the contrast between the ugliness of sin and the obedience of Christ was turned into a great public spectacle. God focuses our gaze on to the two sides. We see the jeering spectators, the callous soldiers and the scheming rulers. Then we dwell on the loving, forgiving, holy Son whom He sent to show us how to live. He calls on us to change places. We have to confess our guilt, and move across from the ranks of God’s enemies to the family of Jesus Christ.

It is an act of faith as clear as that displayed by the poisoned Israelites as they sought to escape the effects of the serpent’s bite. On the face of it, it is just as unlikely to work. What can a dying carpenter from an obscure village in Galilee do for me, the sceptic will urge. Thousands were crucified. Why should this one make any difference to the history of the world? Well, the choice is still ours. If we examine the life of this carpenter, we find the Son of God walking amongst people. When we discover that the very manner of his death was foreshadowed by the bronze serpent, 1500 years before it happened, that should make us think very hard indeed. Since the earliest days of Christianity there has only been one answer: to repent, and be baptised into the Lord Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of sins (Acts 2:38).

That brings us to the smitten rock. The wilderness journey of the Israelites is likened by the Apostle Paul to the pilgrimage of the followers of Christ. They ‘were baptized into Moses,’ he says, ‘in the cloud and in the sea,’ just as the Christian life must start by baptism into the name of Jesus. And he continues, they ‘drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was Christ’ (1 Corinthians 10:2–4). The life-giving water that sustained the Israelites came from a stricken rock. And from the smitten body of the Lord came the blood and water that preserve his people from eternal death. ‘Whoever drinks of the water that I will give him will never be thirsty again. The water that I will give him will become in him a spring of water welling up to eternal life’ (John 4:14).

How neatly and completely does the Bible hang together. It teaches us by pattern and picture the plan and the will of God. From Genesis to Numbers, from John to Corinthians, the message is the same. God grant us wisdom and patience, to complete the journey, and win the prize of eternal life.

David M Pearce