Pontius Pilate was the Roman governor who sentenced Jesus Christ to death. This is an imaginary memoir, but it is based on the facts as we know them from the Bible and archaeology. The Bible verses are given for reference. You can catch up with Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

Part 3

THERE WAS NOTHING I could do. I had given them the choice, they had decided, I hated the situation but I could not go back. I gave the order for the release of Barabbas, turned my back on the mob and stalked back into the Praetorium. The prisoner was dragged after me (Matthew 27:27–29).

I sat weakly on my seat. This was a part of the proceedings which I often enjoyed, but today I had no stomach for it. The hall was filling with soldiers, word had got round and anyone who was off duty was gathering to watch the sport. The king of the Jews! This was an opportunity for the lads to show what they thought of that.

The man stood there, meek, trembling slightly, head down, like a lamb in the middle of a pack of wolves.

They hauled off his tunic, cuffed his wrists and fastened him to the scourging pillar; then to the shouts and cheers of the assembly his back was whipped till the skin was in shreds and each blow spattered the floor with blood.

When the captain judged that it was unsafe to continue for fear the prisoner would die, they dragged him back into the middle of the hall. Someone had been to collect a bunch of thorn branches, and there were whoops of glee as they were twisted into a makeshift crown, which was then jammed on to the prisoner’s head to a raucous cheer. He staggered and buckled, rough hands held him up, blood spurted from his forehead and coursed down his temples.

They flung the purple robe around his shoulders and jammed a reed into his hand as a mock sceptre. Someone shouted “Hail, King of the Jews!” and the crowd roared with laughter. The captain dropped to his knees in front of the prisoner and did obeisance, his men cheered, then he stood up and thumped him hard in the stomach. They started stamping and chanting, like a pack of dogs jostling around their prey. Someone snatched the reed from his hand and cracked it over his head, and the hall rang with another cheer. They started to take it in turns to kneel before him then spit in his face (Mark 15:16–19).

The captain was watching expertly, ready to step in before the prisoner was killed. But before he did so I couldn’t take any more. I rose to my feet and barked “Stop that!” The soldiers withdrew instantly and stood to attention. I beckoned to the two who were supporting the prisoner, and strode out to the portico.

The priests were waiting, expectant.

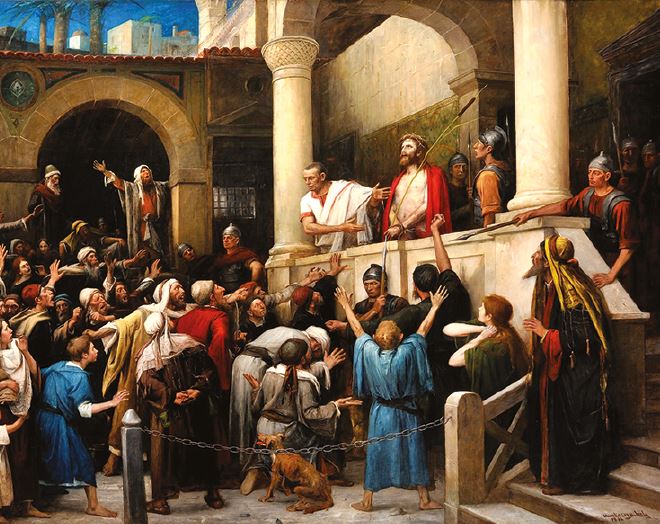

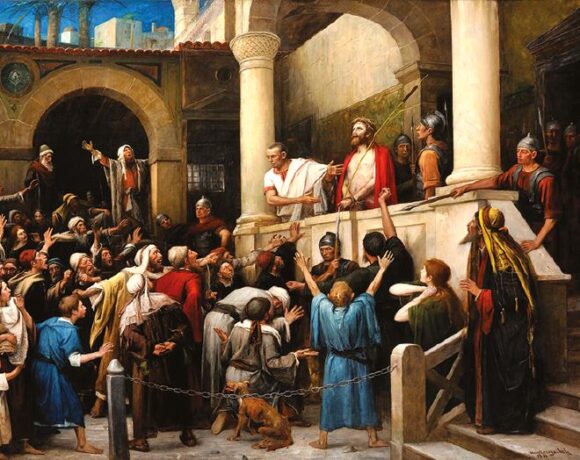

“Behold,” I said, “I am bringing him out to you, that you may know that I find no fault in him.” The prisoner was shoved out on to the pavement, his escort withdrew and he stood there before them, haggard and blood-soaked, his face and his body twisting with fatigue and pain, wearing the crown of thorns and the purple robe (John 19:5–16).

“Behold the man!” I said. Perhaps I was appealing to their sense of pity. Instantly they bellowed, “Crucify him, crucify him!”

I did not want to be part of this. “You take him and crucify him,” I shouted over the tumult, “for I find no fault in him.”

One of the priests launched himself at the balustrade and yelled back at me while he jabbed an angry finger at the prisoner: “We have a law, and according to our law he ought to die, because he made himself the son of God!” The others cheered and jeered, shaking their fists at me and my men.

I knew that the accusations were false. I knew there must be a special reason for such vitriolic hatred. There was nothing in the demeanour or behaviour of this man which gave me cause to think there was any insincerity about him, and it was obvious he was no ordinary man—in all my life I had come across nobody like him. And now they told me that he claimed to be the son of a god.

I was suddenly very afraid. I retreated into the hall. They dragged the prisoner after me, he swooned and one of the soldiers hoisted him to his feet. His head lolled to one side, the soldier grabbed his beard and jerked his face round to look at me.

“Where are you from?” I demanded.

One eye was completely closed under its throbbing black bruise, the other was smarting and bloodshot, but when he had managed to focus he regarded me patiently. I leaned close and hissed, “Are you not speaking to me? Do you not know that I have power to crucify you, and power to release you?”

He spoke quietly, in painful laboured gasps: “You could have no power at all against me unless it had been given you from above.” Through the blood and sweat which oozed down his face his eye flicked in the direction of the waiting priests. “Therefore the one who delivered me to you has the greater sin.” Then he fixed me again with his gaze.

I pulled myself away and shouted for my secretary. “Get this man out of here. I want a platoon at the door on Bakers’ Street immediately, get him down the rear stairs and get him out of the city.”

My secretary nodded and hurried away.

I bawled at the gathered soldiers: “To your posts, now!”

Soldiers snapped to attention and the Praetorium began to empty. I gathered my cloak and motioned to the guards who were supporting the prisoner to follow me. But at that moment a shout arose above the din of the mob outside: “If you let this man go, you are not Caesar’s friend. Whoever makes himself a king speaks against Caesar!”.

I stopped. My guards stopped. These rebellious Jews who made no secret of their disrespect for the Emperor and all he stood for—were they really prepared to report me to Rome? Perhaps they were aware that Sejanus had fallen out of favour at court and my situation was precarious.

I stormed out to the portico and faced the mob. Silence fell. There at the balustrade stood the High Priest Caiaphas, smirking triumphantly. I glared at him. I sat down with as much dignity as I could muster, and called for the prisoner.

An innocent man. A divine man. But was he worth my career? There was nothing I could do.

Humiliated and angry, I pointed at the prisoner: “Behold your King!”

Instantly the mob resumed shouting, “Away with him, away with him! Crucify him!”

“Shall I crucify your King?” I taunted them, bitterly.

The chief priests shouted “We have no king but Caesar!”

And that was one consolation I drew from that day’s hideous events—no amount of bullying I could have inflicted would ever have extracted from them such a declaration of loyalty to the Emperor. I wonder whether they will live to regret it.

I rose to my feet, turned my back on the mob, gave the order that the prisoner was to be crucified, and walked inside.

Katie Cabeira