MOSES STARED AGHAST at the bright blood seeping into the sand. He had killed a man. For a moment he stood still, paralysed by the enormity of his deed, and then, panicking, fell to his knees and began to scrabble a shallow grave. Soon the Egyptian taskmaster’s body was covered from sight, and only the footmarks showed where they had fought in the hot sun.

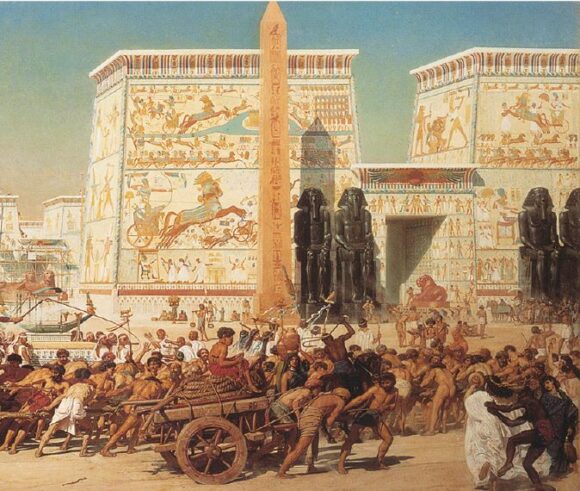

It had been a fateful day for Moses. He was 40 years old, in his prime, strong, resourceful and self-confident. Brought up as the foster child of Pharaoh’s daughter, he had enjoyed the privileges of his station, and a real taste for luxury and power. Lately, however, a change had come over him. Although the crowds cheered as enthusiastically as ever when he drove out in his splendid chariot, he hardly seemed to hear them. He found himself drawn repeatedly to the new cities his foster grandfather was building. Rameses was a great man for monuments, and Moses’ fellow courtiers would rave over the soaring towers and buildings. But Moses saw only the grimy, cursing, toiling slaves who heaved the huge blocks and pillars into place.

He felt strangely uncomfortable. He kept telling himself they were his own people. Why was he not amongst them? While he was still being brought up by his true parents, before entering Pharaoh’s house, Moses had learnt that he had the blood of Abraham in his veins. His father had recited to him the great adventures of his forefathers, and how the God of Israel had rescued them from many dangers. He knew his people had a land of their own, far away across the desert. We know he remembered those lessons well, because years later he named his own son to commemorate his father’s faith: ‘Eliezer’, which means ‘the God of my father was my help’ (Exodus l8:4).

Joseph the Saviour

Of those stories his parents had told him, there was one which he would find particularly meaningful now as he compared his soft life with that of his fellow countrymen. Joseph, the son of Jacob, had been an Israelite in Pharaoh’s court, centuries before. Guided by God and His wisdom he had delivered the people from starvation during a great seven-year famine. Moses’ father believed that Joseph had been put there by God to keep Abraham’s descendants alive. Moses could not help wondering at the strange circumstances behind his own upbringing. He had been snatched from the cradle into the palace and elevated to a key position in the kingdom.

Seeing the brutality inflicted by the Egyptians upon people of his own flesh and blood, he felt compelled to believe that he must have been put where he was so that he could deliver his people from their bondage.

One striking prophecy had been given to Father Abraham. His descendants, the angel had told him, would be settlers in a foreign land, and would be slaves there, and oppressed (Genesis 15:13). Undoubtedly this prophecy had come true. But it went on to say that in the fourth generation they would come back to the land of Canaan (verse 16). By any reckoning, that event was now due.

Moses was in a turmoil. Nightly he considered what he should do. Should he break with the court, defy Pharaoh, and go out to his people to tell them he was their champion? Or should he stay put, stifling his conscience, and enjoy the pleasures, the power and the status that were his royal heritage? The decision was not easy. To rebel would be an insult to his adopted family, after all they had done for him. Pharaoh would be furious. Suppose the attempt failed! Suppose the God of his father let him down, and he was ignominiously arrested! It was a tremendous risk to take.

The reproach of Christ

To his eternal credit, Moses made a decision. He compared the future that lay before him in Egypt with the reward that the God of Israel had offered to his forefathers, and chose the latter as more worthwhile.

We know from the book of Hebrews exactly what went through his mind: “By faith Moses, when he became of age, refused to be called the son of Pharaoh’s daughter, choosing rather to suffer affliction with the people of God than to enjoy the passing pleasures of sin, esteeming the reproach of Christ greater riches than the treasures in Egypt; for he looked to the reward” (Hebrews 11:24–26). Moses never knew Jesus Christ as a person, but he was prepared to suffer the same hatred from his contemporaries as the Christian Jews to whom the book of the Hebrews was written. They knew what it was to suffer for Christ, and Moses trod the same path before them.

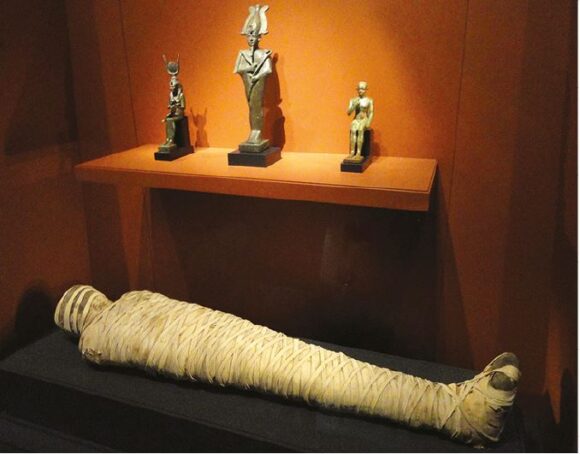

What the writer of the Hebrews is emphasizing in this passage is the difference between the two rewards. ‘The passing pleasures of sin’ is a telling description of the sensuous delights that awaited a grown man in Pharaoh’s household. But pleasures inevitably cloy, and degenerate into the emptiness and disillusionment of old age. The Pharaohs were embalmed to preserve their bodies and buried with dazzling splendour and priceless treasures—but when their graves are opened, the treasures are there for the taking and their bodies are shrivelled. The Pharaoh’s death was no less final than the death of anyone else.

Moses weighed up the value of both rewards. He decided that treasures and pleasures alike were worth nothing compared with the promise of God to His faithful children (Genesis 12:1–3). With vision and courage, Moses chose to strip off his robes and step out to visit his people.

That step is one we must all make, if we wish to please God. As Jesus said, we cannot serve God and mammon (Matthew 6:24). There has to come a day of departure, a turning of our back on an old Iife of sin, and a standing up to be counted with the people of God.

Moses the Saviour

Moses’ opportunity came when he saw a lonely Israelite slave being savagely beaten by his overseer. The helplessness in the man’s eyes and the gross injustice of his case stirred Moses’ anger. The record says “he looked this way and that way, and when he saw no one, he killed the Egyptian and hid him in the sand” (Exodus 2:12). So far as we know from the Bible account, it was the first and the last time he ever killed a man. But he had made his point. He went home to let the news spread through the Israelite encampment that he was on their side. For the moment he was safe from the Egyptians, because he had concealed his victim. Though the overseer would be missed at nightfall, time was on his side.

The next day was the worst Moses ever experienced. He went out again full of hope, to visit his people. He really believed they would rally round him, and accept him as their God-given saviour. Recalling the event two thousand years later the martyr Stephen declared “he supposed that his brethren would have understood that God would deliver them by his hand” (Acts 7:25). His faith in human nature, and in God, was rudely shattered. This is what happened: seeing two Israelites quarrelling, he tried to separate them, only to receive a mouthful of abuse: “Who made you a prince and a judge over us?” shouted the man who was in the wrong. “Do you intend to kill me as you killed the Egyptian?” (Exodus 2:14). It was a stinging blow to his pride. They knew the risk he had taken for them, but they had no respect for him at all, and were not prepared to have him as their leader. The news of the murder was out. He realised the Israelites would not support him, and the Egyptians would soon be seeking retribution. Bitter, disillusioned, and in turn afraid, he crept out of the field, gathered a few essentials together, and set out for the wilderness where he would be safe from Pharaoh’s wrath.

The Fugitive

Pity him, as he fled friendless and alone. Many great men of God started their careers with disaster dashing their faith. Joseph, David, the Apostle Paul—they all found their self-confidence eliminated so that they would learn to depend on God. Faith is a painful virtue to acquire, and Moses, at age 40, had hardly begun to know the God of Israel Who had seemed to fail him in the hour of need. If you feel depressed or low because God seems to be silent and your Iife is in ruins, take heart. In time Moses became one of the greatest Bible characters It would be another 40 years before he was both wise and humble enough to lead his people from slavery, but those decades of waiting in the wilderness were crucial to the making of the man. Ponder Moses’ own Psalm, in which he speaks of the affliction we all have to suffer, and the secret of waiting for God:

So teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom… Oh, satisfy us early with Your mercy, that we may rejoice and be glad all our days! Make us glad according to the days in which You have afflicted us, the years in which we have seen evil (Psalm 90:12–15).

David M Pearce