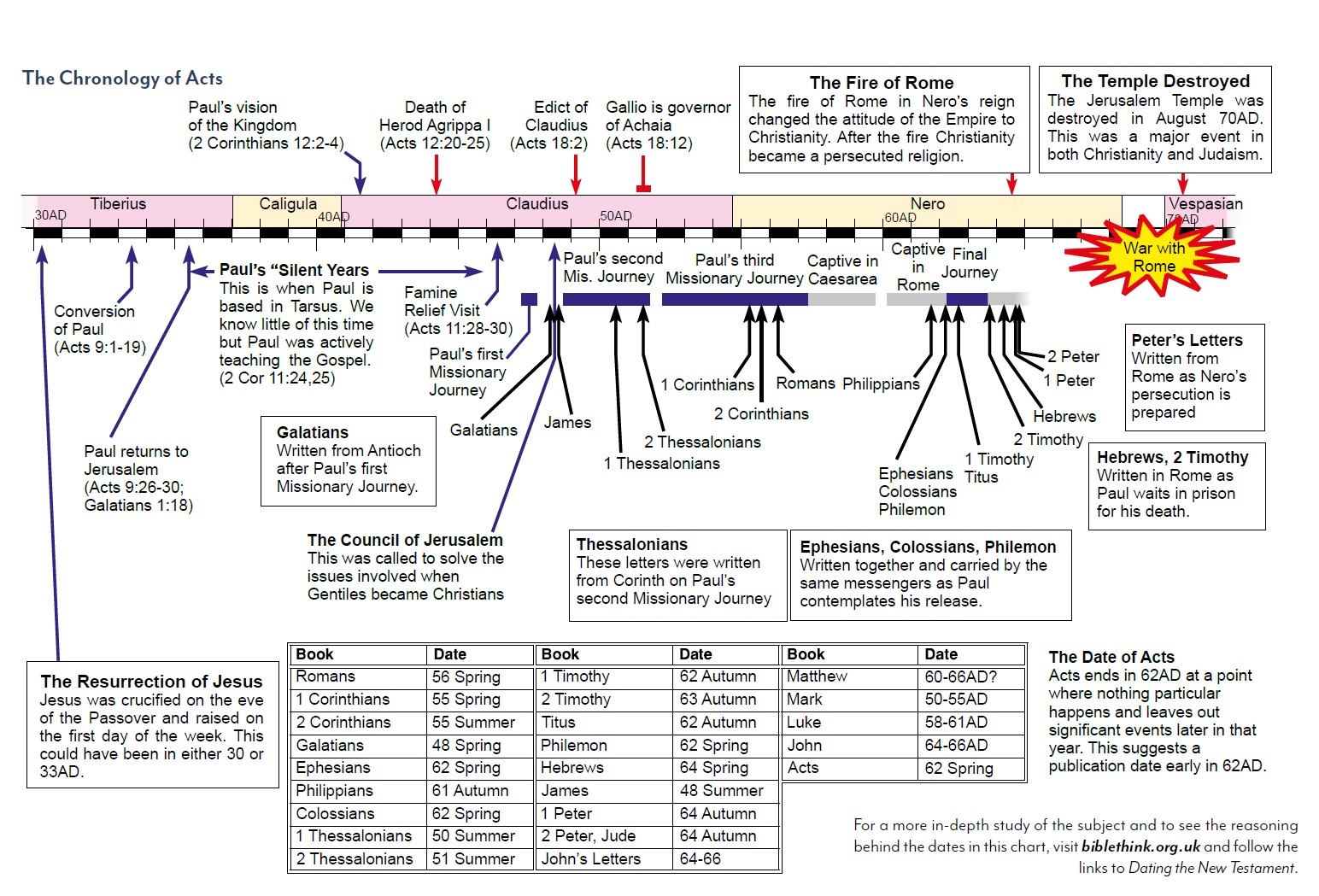

WHEN WE study the New Testament (the second part of the Bible which deals with the life of Jesus and the activities of the early church), it’s useful to determine the date at which each of the documents in it was written. This is an involved study, but it leads to a very clear picture of how the letters in the New Testament were written and what was going on at the time that each was written.

The study of the chronology of the New Testament involves comparing details in the letters with events in the book of Acts, and other historical events whose date can be established from archaeology or reference to ancient documents outside the Bible. The result is that we can be confident of the date of almost all of the letters to within a single year, and many of them to within a couple of months.

The single fact that makes it relatively simple to identify the dates in Acts is that travel became almost impossible in the winter. Ships would not sail for more than very short distances because of the problem of navigation in poor visibility, and it was very difficult to travel overland because the winter rain swelled the rivers and rendered them impossible to ford. The apostles would be forced to stay where they were in the winter.

The Time Framework

Two key events which are mentioned in Acts and for which we have definite dates from archaeology are the edict of Claudius expelling Jews from Rome, which was made in early 49ad, and the accession of Gallio as governor of Achaia, which happened in 51ad. The edict of Claudius is mentioned in Acts 18:1–2 and the accession of Gallio appears in Acts 18:12. This fits in well with Acts 18:11 which tells us that Paul stayed in Corinth for 18 months before he appeared before Gallio.

We can put this together with the narrative in Acts to show that Paul arrived back in Antioch at the end of 51ad and then set off for Ephesus on his third missionary journey in 52ad. He spent around two and a half years in Ephesus (Acts 19:8–10) which takes us to the winter of 54ad. Early in 55ad he sent out Timothy and Erastus (Acts 19:22); he then left shortly after Pentecost (late May) (1 Corinthians 16:5–6).

Paul returned to Jerusalem in the spring of 57ad; he was hoping to arrive there before Pentecost (Acts 20:16). He was arrested in Jerusalem and taken to Caesarea, which takes us to 59ad. At this point the governor Felix handed him over to Festus and later in the year Paul was sent on his voyage to Rome. He was shipwrecked at the end of the travelling season of 59ad and arrived in Rome in the early spring of 60ad. Acts 28:30 tells us that he spent two years in Rome; it seems that Acts was written at this point, which is the spring of 62ad.

The earlier part of Acts can be dated by a similar process. There was famine in Judea in 46 and 47ad; Paul and Barnabas went on a visit to Judea to relieve this famine (Acts 11:28–30). They would return to Antioch in the autumn of 46ad, having visited Jerusalem, and set out on the first missionary journey in 47ad, returning the same year. This leaves 48ad for the Council of Jerusalem. Paul would set off for his second missionary journey the same year and overwinter in Galatia, probably in Antioch in Pisidia.

Dating the Letters

The date of the letters in the New Testament can be established by comparing the details in them with this framework. For example, we can date 1 Corinthians by noting that it was written after Timothy and Erastus had left Paul in the spring in which he left Ephesus, that he had not left yet, and that he hoped to leave shortly after Pentecost (1 Corinthians 16:5–8). This places 1 Corinthians in the period between Passover and Pentecost, 55ad, as Paul was preparing to leave Ephesus.

The date of Galatians can be worked out from its references to Paul’s visits to Jerusalem. He made one visit three years after his conversion (Galatians 1:18) and a second visit 14 years after his conversion (Galatians 2:1); this would be the famine relief visit. No other visits are listed, which means that Galatians was written before the Council of Jerusalem. As Paul founded the congregations in Galatia on his first missionary journey, the year before the Council of Jerusalem, the letter must have been written either late in the year of 47ad or early in 48ad.

This enables us to date Paul’s visits to Jerusalem. We know that the famine relief visit must have been in 46ad; this is described as being 14 years after Paul’s conversion. Given that the ancient convention often involves counting in parts of years and including the first year in the count, this would place Paul’s conversion in 33ad and his first visit to Jerusalem after this in 35ad.

The study of the chronology of the New Testament involves paying tremendous attention to the details in the text. The fact that the letters do fit into the framework of Acts with such precision is itself a witness to the accuracy with which Acts is recorded, and the fidelity with which it has been copied and passed down to us since that time.

John Thorpe

For a more in-depth study of the subject and to see the reasoning behind the dates in this chart, visit biblethink.org.uk and follow the links to Dating the New Testament.