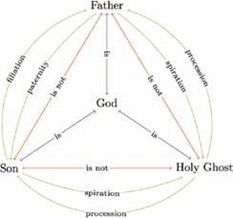

THERE IS A CREED that many churches hold as essential to salvation, and part of it reads:

‘We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in unity; neither confounding the Persons: nor dividing the Substance. For there is one person of the Father, and another of the Son: and another of the Holy Ghost. But the Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, is all one: the Glory equal, the Majesty co-eternal… And in this Trinity none is afore, or less than other; But the whole three persons are co-eternal together; and co-equal… He therefore that will be saved, must think thus of the Trinity’ (Athanasian Creed).

I confess that this creed has always baffled me. I know that the doctrine of the Trinity is held very dear by many people, and I am aware that questioning it can cause upset. But we need to test everything by the Bible.

The Bible does contain lofty concepts which require thought to properly understand them, such as ‘the atonement’ (see the article in Issue 1656)—but these concepts are clear and logical, and it is easy to explain and understand them using Bible vocabulary. The idea of the Trinity is different: it requires mental gymnastics to understand it, and it can only be properly explained using vocabulary that does not occur in the Bible.

The Bible is the Authority

Hundreds of times the Bible has phrases such as ‘Thus says the Lord’ (for example Jeremiah 2:2), to emphasise that the book is about God’s dealings with humankind. It commences, ‘In the beginning God…’ (Genesis 1:1). His mightiness is impressed upon us as we think of the glories of His creation: ‘O Lord, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth! You have set your glory above the heavens’ (Psalm 8:1).

We cannot even begin to understand a Being so ageless, but throughout the Bible the thought is repeated, for example ‘who alone has immortality, who dwells in unapproachable light, whom no one has ever seen or can see. To him be honour and eternal dominion. Amen’ (1Timothy 6.16).

I have looked in the Bible for the word ‘trinity’. I searched thoroughly (it’s easy enough to do with a concordance or a Bible app), and the word was nowhere to be found. Wherever did the term come from?

Well one can certainly find the word God, and the words Jesus Christ, and Holy Ghost (most modern translations use the words ‘Holy Spirit’). But nowhere do we find that God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit are co- equal. So, from where do we get the idea of a Trinity?

Church history shows that it gradually developed, until it was finally defined around 400 years after the time of Christ in a statement called the Athanasian Creed, part of which is quoted above.

The Father

The prophet Isaiah asks, ‘To whom then will you liken God, or what likeness compare with him?… It is he who sits above the circle of the earth, and its inhabitants are like grasshoppers; who stretches out the heavens like a curtain, and spreads them like a tent to dwell in (Isaiah 40:18, 22). Words cannot describe the greatness of God: ‘I am the Lord, and there is no other, besides me there is no God’ (Isaiah 45:5).

The thought is repeated so often that it is not difficult to understand why the concept of the Trinity is incomprehensible to religious Jews. It is a great stumbling- block to their acceptance of Christianity. Their prophet is emphatic:

For thus says the Lord, who created the heavens (he is God!), who formed the earth and made it (he established it; he did not create it empty, he formed it to be inhabited!): “I am the Lord, and there is no other” (v. 18).

The Holy Spirit

What is the Holy Spirit? It is the description of God’s power, and we read, ‘If he should set his heart to it and gather to himself his spirit and his breath, all flesh would perish together, and man would return to dust’ (Job 34:14–15); Jeremiah adds, ‘Ah, Lord God! It is you who have made the heavens and the earth by your great power and by your outstretched arm! Nothing is too hard for you’ (Jeremiah 32:17).

Is the Holy Spirit a person? Let us take an example. You kick a ball. The ball moves by the power behind the kick, but you and your power are one and cannot be separated. Likewise God and His power cannot be separated. The Holy Spirit is the power by which the Almighty formed the universe, made us, demonstrated His glory through angels, and gave His writings to chosen men.

The 18th-Century logician and theologian Isaac Watts wrote, “I can find no verse in the Bible where any word that directly signifies person is attributable to the Holy Spirit… it must be a divine power.”

The Son

Jesus Christ is frequently referred to as the Son of God, but never as God the Son. Trinitarians suggest that this was because the Son divested himself of his God status and became mortal when he was born, then resumed his God status after his resurrection. But the Bible sees things much more simply: God and the angels are immortal. God gave immortality to His Son after he was raised from the dead, and He will give it to us if we are faithful. ‘For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality’ (1 Corinthians 15:53). The idea of an immortal being becoming mortal is alien to the Bible.

This is how the Bible describes Jesus Christ:

Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world (Hebrews 1:1–2).

The fact that the one promised was a Son and an heir indicates that he did not exist beforehand. The angel Gabriel declared to Jesus’ mother Mary, ‘He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. And the Lord God will give to him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob for ever, and of his kingdom there will be no end’ (Luke 1:32–33). When the baby Jesus was born the angels sang, ‘Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace among those with whom he is pleased!’ (Luke 2:14).

Jesus Christ is a unique man. He was flesh and blood, exactly like us: ‘Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same things, that through death he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil’ (Hebrews 2:14). But he was different from us in that God was his father, and because of that he had a strength to resist ‘the devil’ (his human nature’s propensity to sin) which no one else has ever had. He never did sin, and therefore he was able to offer himself as a perfect sacrifice to be our Saviour.

The fact is, he was capable of sin. He could have given in to the devil. But he did not: ‘For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin’ (Hebrews 4:15).

In this he was different from God: ‘Let no one say when he is tempted, “I am being tempted by God”, for God cannot be tempted with evil, and he himself tempts no one’ (James 1:13).

So acutely did the Lord Jesus perceive this difference between himself and his Father that he would not even allow people to call him good, and said, ‘Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone’ (Mark 10:18). He stressed constantly that he was completely dependent upon a God Whom he taught was supreme. He reiterated the Old Testament command, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and

with all your soul and with all your mind’ (Matthew 22:37). Of his second coming he was clear, ‘concerning that day or that hour, no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father’ (Mark 13:32).

Difficult Passages

John’s Gospel contains language and idioms that have led some to assume that it is presenting Jesus Christ as co-equal and co-eternal with God. For example ‘I and the Father are one’ (John 10:30). This does not mean that they are part of the same godhead, it means they are one in purpose and outlook. As Jesus explains later, he wants all his followers to share this oneness: ‘And I am no longer in the world, but they are in the world, and I am coming to you. Holy Father, keep them in your name, which you have given me, that they may be one, even as we are one’ (John 17:11).

When you read it carefully, you see that John’s Gospel is portraying the beautiful relationship between God and His Son. Jesus said, ‘My food is to do the will of him who sent me and to accomplish his work (John 4:34). There are 44 occasions in John’s Gospel on which it is emphasized that Christ was ‘sent’.

For the Father loves the Son and shows him all that he himself is doing. And greater works than these will he show him, so that you may marvel… For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself (John 5:20, 26).

There is no sense of equality. God is the fountain of all life, and He gave life to His Son.

In what way was the Lord Jesus sent? Does it mean he came from a previous life? Later John gives the answer as Jesus prays to his Father about his disciples: ‘As you sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world’ (John 17:18).

The Sacrifice of Christ

When we come to look on the Lord’s agony of mind in Gethsemane, and hear his heartfelt plea to his Father, we realise that this was a man dreading what the future would bring. What man would not be the same in similar circumstances? We can only look on with reverence as his sweat falls like great drops of blood upon the ground (Luke 22:44). His agony is such that his heart-rending plea is ‘Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me. Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done’ (v. 42). Two distinct wills are shown to us: the will of God, and the will of the Son appalled at the prospect before him. Yet he ended his life with perfect obedience, that we might have a sinless representative who could open the way to God for us.

Perhaps you have seen the portrayals of Christ on his cross, with gentle eyes gazing calmly heavenwards. It was not like that. It was a fiendish torture that brought his all too brief life on earth to a premature end. Six hours on the cross in searing agony would be enough to make any man blaspheme outrageously, and even the Saviour in the fierceness of his suffering cried, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ (Matthew 27:46).

Surely, to say that Jesus was God is to render his courage, love, submission and agony meaningless, and to strip his terrible sacrifice of its meaning.

Because of his faultless sacrifice Jesus Christ was raised from the dead (Acts 2:24), and rose to the side of his Father to act as the mediator for his people: ‘For there is one God, and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus; who gave himself a ransom for all’ (1 Timothy 2:5–6). He is now in an exalted place, but even now he is not equal with his Father.

God is one, the Almighty and Eternal; and Jesus Christ is His beloved Son who is worthy of all praise and honour:

‘God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father’ (Philippians 2:9–11).

Ken Clark