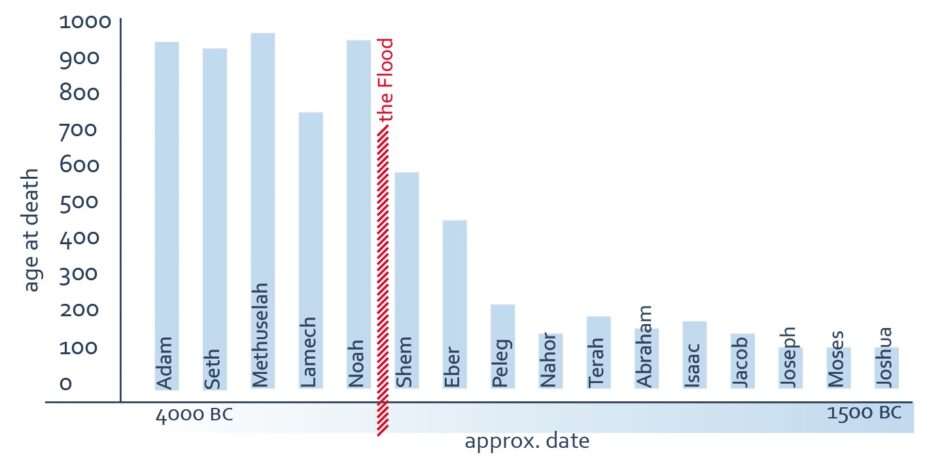

You may have heard of Methuselah, the oldest man who ever lived. He lived to the age of 969 (Genesis 5:27). But it is surprising to find that most of his contemporaries likewise survived to a very great age. Enos, for example, was 905 (Genesis 5:11), and Jared 962 (verse 20), and most others died after at least five hundred years.

The graph below shows people’s stated longevity generation by generation from Adam to Moses. It continues steady around the 900-year mark right down to the time of the Flood, at the time of Noah in Genesis chapter 6. At this point it plunges steeply downwards for about six generations, then levels out to 80 to 100 years by the time of Moses. This is not the place to discuss the possible physical explanation for the dramatic change in lifespan after the Flood, but the phenomenon draws our attention to the frightening potential for evil possessed by a criminal who could live for hundreds of years. Think of the time they would have to perfect their techniques of robbery, extortion and violence! No wonder the earth in the time of Noah is said to have been ‘corrupt in God’s sight, and the earth was filled with violence’ (Genesis 6:11).

But think, too, of the frustration and pain we can encounter in these mortal bodies. To live for ever would be no blessing in the bodies we have today. But God has promised His children a new, perfect body in His Kingdom (Mark 12:25). Only then will we be set free from our slavery to sin, with its weary battle of the ‘spirit‘ against the ‘flesh’ (Romans 8:1–11).

The Apostle Paul himself was permanently afflicted by a painful disease (2 Corinthians 12:7–9). He tired of the constant struggle against sin and its effects. ‘Wretched man that I am!’ he complained, ‘who will deliver me from this body of death?’ But the answer follows at once: ‘Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!’ (Romans 7:24–25). For Paul, the victory of Jesus over sin had brought him the promise of resurrection and a body like the new body of the risen Christ (1 John 3:2).

Lamech’s Firstborn

That struggle against the curse, so keenly felt by Paul, brings our thoughts back to Genesis and to the next notable character in the generations following Seth. Lamech, son of Methuselah, was 182 years old when his first child was born (Genesis 5:28). Like Paul, he felt depressed and bowed under the burden of mortality. It was a great joy to him when they told him his wife had borne a son.

Perhaps it made him think of the deliverer promised to Eve, the offspring of the woman who would conquer the curse for mankind (Genesis 3:15). At any rate he decided to call the baby ‘Noah’, which means ‘Rest’, for, he said, ‘Out of the ground that the Lord has cursed, this one shall bring us relief from our work and from the painful toil of our hands’ (Genesis 5.29).

He may seem only to have been thinking of the practical help his son could one day give him on the farm. But it is a remarkable fact that Noah was destined to become, in a sense, the saviour of the human race. Like Jesus (whose destiny stretches into our own future), he was to be head of a family of righteous people who would survive the forthcoming day of judgement, and repopulate a cleansed and restored earth.

Lamech must have died very shortly before the Flood (compare Genesis 5:30 with 7:11). He would be aware of God’s warning of the impending catastrophe and His instructions to Noah to prepare by building an ark (Genesis 6:13–21). He would have seen the preparations Noah made to preserve life through the waters of death. He would know now that God’s purpose, the promise to Eve, was not going to be cut off by the coming catastrophe. The line of Eve’s offspring was going to be preserved through his own God-fearing son.

Like his fathers, Lamech died in faith. He is asleep even now in the peace of death that ended his toil and tears. But he awaits with confidence another, more permanent rest. ‘So then,’ as the author of the Hebrews writes, paraphrasing Lamech’s prophetic words, ‘there remains a Sabbath rest for the people of God’ (Hebrews 4:9). That perfect rest will be the Kingdom of God, that will finally take away the curse that came with Adam’s sin.

Intermarriage

Sixteen centuries had passed since Adam and his wife had been expelled from the Garden of God (Genesis 3:24). The population of the earth had grown slowly in the early years, but now it had begun to expand at a spectacular rate. The descendants of righteous Seth had not multiplied as fast as Cain’s offspring. For most of this period it seems they had kept themselves strictly apart. Unhappily, there was now a change.

It appears that intermarriage with Cain’s family, the ‘sons of men’ had always been frowned upon as a dangerous step, a sign of neglecting the holy way of life established by the great patriarchs. But as Seth, Methuselah and Lamech died out, and their influence disappeared, a new generation arose with weaker faith and fewer inhibitions. ‘When man began to multiply on the face of the land and daughters were born to them, the sons of God saw that the daughters of man were attractive. And they took as their wives any they chose’ (Genesis 6:1–2).

The effect was disastrous. Instead of the good influence of the Sethites uplifting and reforming the descendants of Cain, as they may have hoped, the opposite was true. The intermarrying of the two families of humankind produced offspring of tremendous physique, renowned for their stature and might in war, but as depraved as Cain in their selfish greed and arrogance. With the rest of humankind, they treated the generous and patient God with contempt.

There is a lesson here which is repeated elsewhere in the Bible. To choose a marriage partner merely because of physical attraction is a great mistake. Solomon was a connoisseur of beauty. Yet he eventually admitted, ‘Charm is deceitful, and beauty is vain’ (Proverbs 31:30). Marriage is set out in the Bible as a lifelong contract, lasting beyond the years when merely physical attraction will pall. Nor will a difference between the partners in religious beliefs automatically resolve itself with time. Ahab King of Israel married Jezebel, the charming but idolatrous princess of Zidon (1 Kings 16:31). Her introduction of Baal worship to Israel stained a whole century of the nation’s history.

Time for Judgement

With the degradation of the family of Seth, there was no redeeming feature left to sweeten the seething mass of humanity upon which the Lord gazed with sorrow. ‘Now the earth was corrupt in God’s sight, and the earth was filled with violence. And God saw the earth, and behold, it was corrupt, for all flesh had corrupted their way on the earth’ (Genesis 6:11–12). ‘Corrupt’ is an ugly word. We use it of a corpse. God had given good, wholesome laws upon which people could base their lives, but they had twisted them. According to some translations, all flesh had corrupted HIS way on the earth.

Eventually, the Creator had had enough. It was time for a clean sweep. He would hose the whole earth down with a flood of water, and cleanse the filth out of His sight. ‘My Spirit shall not abide in man forever,’ he declared, ‘for he is flesh; his days shall be 120 years’ (v. 3).

An alternative translation reads ‘My Spirit shall not strive with man forever’. God’s Spirit striving with flesh is an idea that runs through the Bible. God did not sit back casually while people became engrossed in wickedness, and then suddenly drop on them without warning and blot them out. Throughout those centuries of rebellion, He had been steadily pleading with people to repent. His spirit, through Enoch the prophet, had sounded the warning of approaching judgment (Jude :14–15).

In the last generation, Noah, too, according to the Apostle Peter had been ‘a herald of righteousness’ (2 Peter 2:5). God never destroys people without giving them every chance to repent. And even now, if we take a simple interpretation of Genesis 6:3, He was going to hold off the day of wrath for another 120 years, just in case one or two more might change their way.

It is a very different picture from the harsh and vengeful God of the Old Testament which modern critics of the Bible usually paint. In fact, they are wrong. He always has been ‘merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness’ (Exodus 34:6). These were the characteristics of God revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai. He went on to demonstrate His mercy in His repeated forgiveness of the grumblings and rebellions of the Israelites in the wilderness.

But justice too must have its place, and when people stubbornly harden their hearts, there is no remedy but to punish them. So, the deadline was ringed way ahead in the divine calendar. Meanwhile people butchered their fellows and blood-stained the fair earth.

David Pearce