For 150 days, the earth was deluged. It was no ordinary rain that produced such a deluge. ‘The fountains of the great deep burst forth,’ says the record, ‘and the windows of the heavens were opened’ (Genesis 7:11). It sounds as though subterranean reservoirs of water came out through the mantle of the globe, while that great band of water in the outer atmosphere, described in Genesis 1:7, collapsed inwards at the same time. On the internet there are fascinating scientific explorations of the mechanics of how this could have been brought about. Certainly, a flood that covered the mountains to a depth of over 20 feet (6 metres) and kept them submerged for eight months (Genesis 7:19–20 and 8:5) must have been global in extent.

As we would expect, tales of the worldwide flood remain in the folklore of cultures all over the world. The most complete account of the flood, outside the Bible, is the Gilgamesh Epic, discovered on clay tablets in Babylon. However, its extravagant language does not compare with the Bible. The crisp, matter-of-fact way in which Genesis chronicles the events, with even such details as the days of the month in Noah’s life when each stage began (for example, Genesis 7:11 and 8:3–5), gives us every confidence that here we have the authentic account of what happened, faithfully transmitted from Noah’s son Shem to the descendants of Abraham.

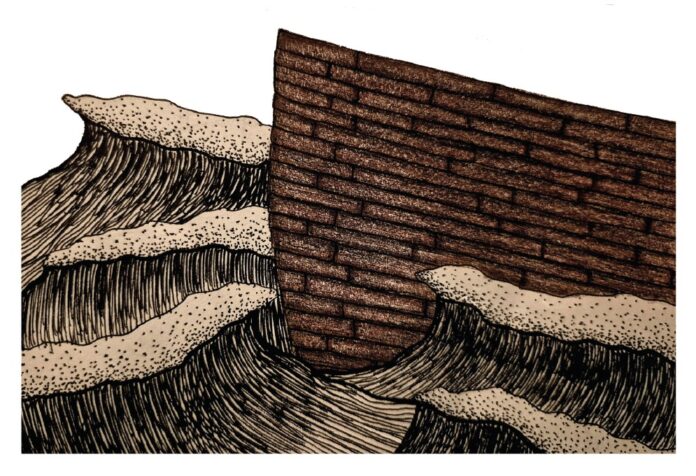

We can imagine the feelings of Noah and his family as the rain hammered down on the ark, and the swirling waters began to lift it off the ground. They could hear the piteous cries of the wretched people outside, seeking, too late, to enter the vessel whose construction they had so recently scorned. They would experience profound relief that out of the millions that died, they had been saved. Those years of toil and sacrifice and jeers had suddenly become intensely worthwhile. As the great timbers groaned under the mighty pressures of the surging waves, Noah especially would have been thankful that he had refused the temptation to skimp on the quality of the materials and workmanship. He recognised that God meant what He said, and by his obedience he saved his household, as the apostle declares in Hebrews 11:7.

A year went by. At last, the months of waiting and confinement were over. The wind dried the swollen waters (Genesis 8:1). Noah sent out first the raven, and then the dove, which returned with an olive twig to start her nest. Now the voyagers knew that vegetation was growing as it had before the flood. Soon the great day came when they could leave the ark.

In deep gratitude for their salvation, Noah offered a sacrifice to God (8:20). He obtained in return a gracious guarantee, upon which our lives depend to this very day. Never again would God blot out life on such a scale. ‘While the earth remains,’ he swore, ‘seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night shall not cease’ (8:22).

With the stability God promised, we are able to plan our lives. If we sow seeds, we expect crops to grow in due course. We never stop to think what would happen if the globe should shift out of true, or some giant comet disturb our orbit round the sun. Yet, on a cosmic scale, we are frightfully vulnerable. Even worse, few of us bother to thank God for our daily bread. Saying grace at table before meals, for example, has gone out of fashion. How about a resolution to say a little prayer of thanks before every meal? You would be following the example of the Lord Jesus, who always gave thanks himself before he ate (for example Matthew 15:36). You would be showing God that, like Noah, you appreciate being allowed to live.

Another great promise was made to Noah and the rest of creation on that day of new beginnings, connected in a delightful way with the rainbow. When, in the months following the flood, the children of Noah noticed the gathering of the clouds before an approaching storm, they might naturally have been afraid that the flood was coming back again. Storm clouds had unpleasant associations for them. To resolve any future doubts, God gave a categorical assurance that there would never again be a worldwide flood. To seal His promise, he gave the rainbow as a token of his good faith. ‘I have set my bow in the cloud,’ he said, ‘and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and the earth. When I bring clouds over the earth and the bow is seen in the clouds, I will remember my covenant that is between me and you and every living creature of all flesh. And the waters shall never again become a flood to destroy all flesh’ (Genesis 9:13–15).

Like a wedding ring on a finger, the bow would be a perpetual reminder of a solemn promise. The soft beauty of those colours, arching from heaven to earth against the background of gloom, still fills us with wonder, even when we have learnt how the rainbow ‘works’ in science at school. How good to think it has a meaning. This was the first great covenant God ever made. Significantly, when centuries afterwards, Ezekiel the prophet was shown a vision of the glory of the Lord, he remarked that round about God’s throne there was a brightness, ‘like the appearance of the bow that is in the cloud on the day of rain, so was the appearance of the brightness all around’ (Ezekiel 1:28). Part of the glory of God is that He keeps His word. If He says He will do something, He does it. And that first covenant, like all the other promises He has made, He has never broken.

David Pearce

(to be continued)