DURING A GAME of football at Rugby School in 1823, so the story goes, William Webb Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it. It was entirely against the rules of the game, but it caught on. The game of Rugby football spread through English public schools and universities, and was exported around the world. In 1900 it was included in the Olympic games, 1987 saw the first Rugby World Cup, and it is now established as one of the world’s most popular sports.

Four hundred years or so before that celebrated game at Rugby School, and eight miles up the road in the village of Lutterworth, another departure from tradition caused shock waves which travelled around the world.

The Word of Life

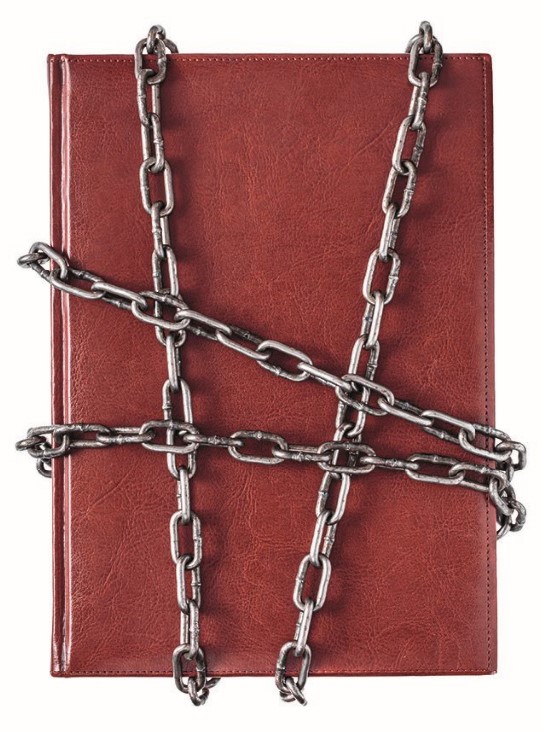

In the 14th Century, Christianity was dominated by the orthodox church which controlled how people lived and what they believed. The Bible was only available in Latin, and only the church hierarchy was allowed to read it.

John Wycliffe was the rector of St Mary’s Church in Lutterworth. He was a scholar and a reformer. He became dissatisfied with the power, wealth and corruption of the church of which he was a member. He read the Bible, and saw that the way the church was organised and operated was completely unlike the original Christian church in the First Century—in fact, the things it taught went against the teaching of Jesus Christ and his apostles. Wycliffe came to the conclusion that the Bible is the only reliable guide to the truth about God, and he railed against the church for making it inaccessible to ordinary people. He determined that the Bible should be available so everyone could read it (or have it read to them). Probably with assistance from other scholars, he produced the first ever translation of the entire Bible into English, which he published in 1382.

Wycliffe’s English Bibles were printed by means of wood blocks, and so their production was arduous. They were distributed by an organisation of devoted supporters, and they were greeted with enthusiasm by a public that was hungry to know what the Bible really said.

The church was furious. It saw Wycliffe’s work as a threat to its authority. He was lambasted and harassed. He died of a stroke in 1384, and shortly afterwards the church declared him to be a heretic. His body was dug up and burned, and his publications were banned.

But Wycliffe had been instrumental in beginning a movement which could not be stopped. Increasingly people became suspicious of the church, and unwilling to be told what the Bible said—they wanted to read it for themselves. The early 1500s saw the beginning of the Reformation in western Christianity, which resulted in the rise of Protestantism in its various forms.

The Reformation was a time of turmoil. It was not a straight struggle between the Catholic church and the reformers who wanted to free themselves from its grasp. Inevitably, people being people, it involved political and military ambitions, agendas and vendettas, compromises and betrayals. But running through this turbulent period was the vision of Wycliffe—of a world where people would no longer need to be told what was God’s will, but could read it for themselves. Many people were persecuted, suffered and died for the cause. And Wycliffe’s vision was brought closer to realisation in 1539 when King Henry VIII published his ‘Great Bible’ and ordered a copy to be made available and accessible in every church in England.

The book that was suppressed for centuries is now freely available, in print and online, in hundreds of languages.

The Age of Light

The medieval period in Europe is some- times referred to as the ‘dark ages’. This is apt because it was a period of spiritual darkness. The brilliance of the work of Wycliffe and those like him was that they enabled the light to shine in a world where it had been obscured for centuries. People could at last read for themselves of the life and words of the Son of God, who said ‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life’ (John 8:12).

That’s all history. But this is the 21st Century. There are those who suggest that the world has moved on, and the Bible is no longer relevant today. And even that it’s dangerous because it’s out of step with modern values. In Europe where once people were forbidden to read the Bible, the mood is once more turning against it, even within some churches.

But it cannot be suppressed—it’s out there, and freely available. If you look into it you will discover that it’s unlike any other book—as should be expected, because it’s the Word of God—and you will appreciate what the Psalmist meant when he said, ‘Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path’ (Psalm 119:105). And if you allow it to do the work for which it was designed, you will come to understand the wonder of the Apostle Paul’s words: ‘God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness”, has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ’ (2 Corinthians 4:6).