Pontius Pilate was the Roman governor who sentenced Jesus Christ to death. This is an imaginary memoir, but it is based on the facts as we know them from the Bible and archaeology. The Bible verses are given for reference.

Part 1

THE JEWISH PASSOVER was always a dangerous time. Jerusalem was packed with pilgrims and bubbling with nationalistic fervour. I ensured our garrison was at full strength, and I took up residence in the city myself and I made sure it was known.

This year there was a particular sense of unease. The Jewish rabble were raving about a travelling preacher by the name of Jesus, whom they had made a focus for their discontent with Roman rule. He arrived in the city a week before the feast.

He rode in on the Jericho road, it was a spectacle and half the city went out to watch. They were shouting “Hosanna to the son of David” (Matthew 21:9). I knew who David was, he was a Jewish king. That was tantamount to treason against Caesar. I called the priests in and had stiff words with them about it. I was reassured —they seemed to be no more keen on the troublemaker than I was.

Whatever he was up to, he had the sense to keep a low profile after that. My spies reported that he spent the days talking in the Temple, then at night he’d retreat to an Olivet village (Matthew 21:17). We were braced for an uprising. The cauldron was seething, but it seemed that we were holding the lid on.

It was the night before Passover, very late. A deputation arrived from the priests. It was about Jesus. They said he’d been causing trouble and they’d had no option, they’d apprehended him and brought him in for questioning. He was standing trial before Caiaphas the High Priest as we spoke (Matthew 26:57). I reminded the emissary that night-time trials were illegal under their law. He snarled. I reminded him that he knew the way things worked, and he smiled and slipped a pouch of gold into my hand (Micah 7:3). We agreed that a quick resolution was in all our interests—they’d bring him over first thing in the morning, he’d be hanging by lunchtime, Jerusalem would be a safer place and we could all get on with our lives.

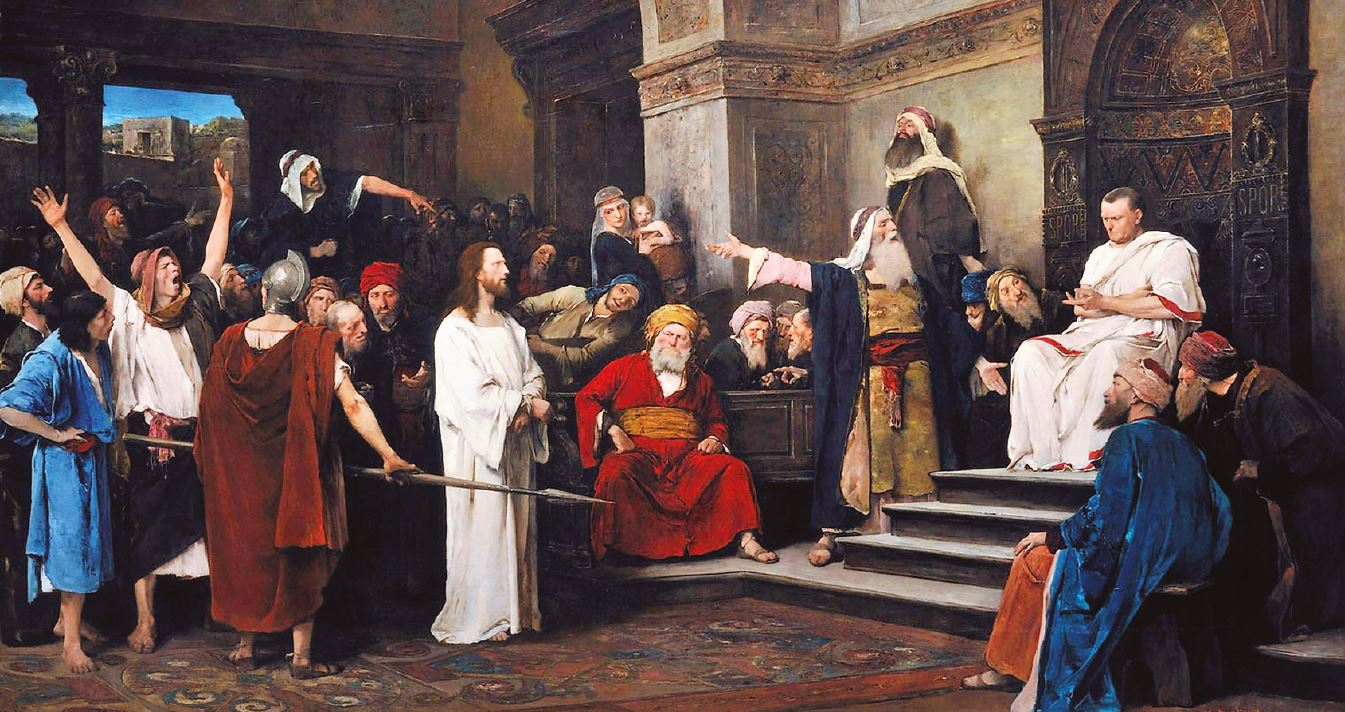

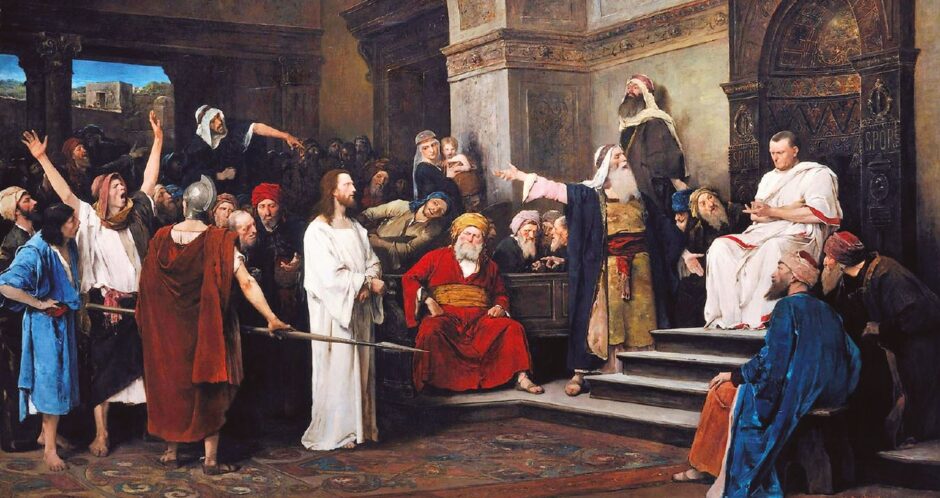

They came at first light, a band of the temple guard bristling with weapons surrounding the tethered prisoner. They wouldn’t enter the Praetoreum so I went out to them (John 18:28). I was acquainted with the Jews’ sensitivities, and I humoured them, it was part of the job.

The crowd parted and the prisoner was thrust forward. I regarded him—haggard and dishevelled, streaked and stained with dirt, but he stood erect and composed. He returned my gaze, and nodded with respect. He did not look like a revolutionary.

The gold chinked in my purse but I played the part: “What accusation do you bring against this man?” (John 18:29).

One of the priests spoke up: “If he were not an evildoer, we would not have delivered him up to you!” (John 18:30). I know that Jews are capable of good manners, but they don’t waste them on Romans.

I looked from the priest to the prisoner, and felt uneasy. “You take him, and judge him according to your law.”

“It’s not lawful for us to put anyone to death,” snapped the priest (John 18:31). He was right, those were the rules, although he knew and I knew that they had no qualms about a swift stoning when it suited them (Acts 7:57–60). But that was not what they wanted now. They didn’t just want the preacher dead, because he was popular with many of the people and that could have made him into a martyr. They wanted a show trial, they wanted him discredited, so he needed public disgrace and the execution of a common criminal. It was a sensible strategy.

“We found this fellow perverting the nation,” the priest said, “and forbidding to pay taxes to Caesar, saying that he himself is Christ, a King” (Luke 23:2). That was the charge—treason. I couldn’t ignore that.

I retired into the judgement hall and had them bring the prisoner inside. I sat down, my officials and guard ranged around me. There alone before us stood the peasant.

I regarded him with interest. He was smarting from a cut to his lip, and I could see a black eye forming, but he was uncannily composed. He was not at all intimidated, by me, by the grandeur of the judgement hall, or by the gravity of the situation he was in. He waited for me to speak.

“Are you the King of the Jews?” I asked (John 18:33).

“Are you speaking for yourself about this, or did others tell you this concerning me?” His voice was measured, courteous and deeply unnerving.

“Am I a Jew?” I snapped. “Your own nation and the chief priests have delivered you to me. What have you done?”

“My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would fight, so that I should not be delivered to the Jews; but now my kingdom is not from here.” With that he dismantled the treason accusation—maybe he was a deluded fanatic, but he posed no threat to the Emperor.

I scratched my head. “Are you a king then?”

“You say rightly that I am a king. For this cause I was born, and for this cause I have come into the world, that I should bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears my voice.”

I was a Roman noble and a politician—truth is a grand concept, but you don’t let it get in your way. “What is truth?” I sneered. Rulership is not about truth, it’s about power. That’s why I’d got where I was, and he’d got where he was.

An interesting chap, it would have been amusing to talk further with him if circumstances were different. However, this was not the time. I hoisted myself out of my seat and strode out to the waiting priests. It wasn’t what they wanted to hear, but I wasn’t going to play their games: “I find no fault in him at all” (John 18:34–38).

Immediately the gaggle of priests erupted: “He stirs up the people!” shouted the spokesman, “teaching throughout all Judea, beginning from Galilee to this place” (Luke 23:5).

Never had I seen them so passionate about one prisoner—what was their problem with this man? This could quickly get out of hand, it was exactly the kind of situation I didn’t want, here at the Passover. I hesitated, then I had an idea: “He’s a Galilean?” Galilee was Herod’s jurisdiction, and the old villain was in residence in Jerusalem for the festival—I’d send the prisoner to him for a second opinion

(Luke 23:7).

I dispatched him under heavy guard to Herod’s palace, and the rabble of priests followed like a pack of hounds baying for the kill. I was glad to see them leave, and went about my business.

Katie Cabeira