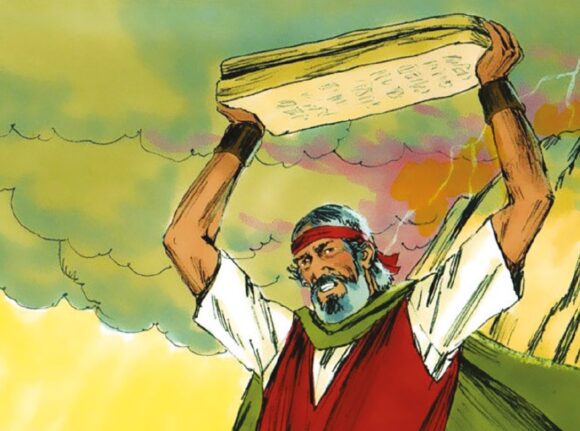

WITH AN OMINOUS clonk the tablets struck the rock. Young Joshua watched in horror. Only that morning they had collected them pristine from the angel of God. The fine inscriptions in economical Hebrew covered both sides of each gleaming stone. Now Moses had deliberately smashed them together on the ground, his face twisted with rage (Exodus 32:19).

Six weeks before, the two men had toiled higher and higher into the cloud-covered mountain, leaving behind the Israelite camp and their families and friends. The days passed quickly. As Moses received each new commandment from God, Joshua probably helped him write it down in a book. Afterwards they were given a detailed plan of the new Tent of Meeting that God wanted the Israelites to build, and instruction in the system of worship to be set up around it. It was thrilling and absorbing, and Joshua would feel elated to be so close to God’s messengers on the holy mountain. The martyr Stephen was later to describe the law as ‘delivered by angels’ (Acts 7:53). Joshua had been privileged to work with them, and with Moses the man of God.

Now, at last, the task was complete. Moses had been given the two stone tablets, inscribed with the Ten Commandments.

They represented a summary and seal of the covenant promise which the people of Israel had made to obey the laws of God. He carried them himself. As they descended rapidly down the mountainside, the familiar Israelite tents came into view. They seemed strangely deserted. Before long Joshua could make out a crowd of people milling about in the centre of the camp. A stab of fear contracted his heart. It could only mean one thing—the Israelites had been attacked by enemies while Moses was away. ‘There is a noise of war in the camp’ he cried, panicking. But Moses’ face was clouded: ‘It is not the sound of shouting for victory, or the sound of the cry of defeat, but the sound of singing that I hear’ (Exodus 32:17–18).

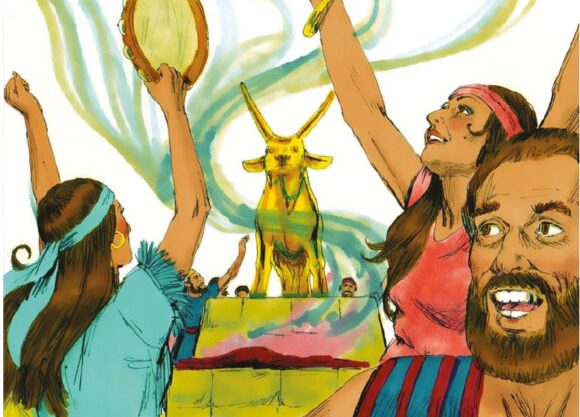

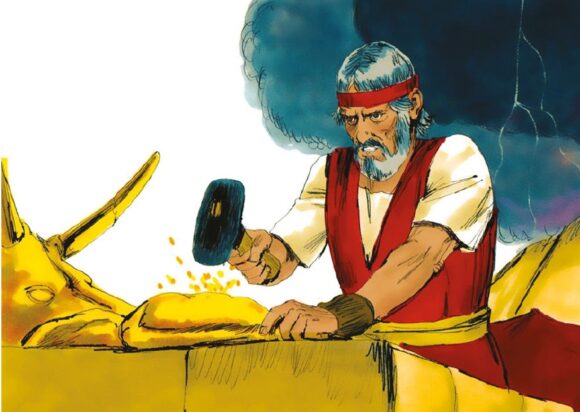

Rounding the rocks, they came upon a scene of shame that Joshua would never forget. There in the camp was a glittering, golden bull calf, just Iike the idols of Egypt they had left behind. The people were dancing half naked and singing loud praises to this heathen god, while Aaron, Moses’ brother, who had been left in charge, stood helplessly before them. On every hand were the remains of an orgy of eating and drinking. Moses hurried down the final slopes and burst into the camp. The dancing stopped, and the Israelites cringed before his wrath. He barked out commands. Soon the idol was purged with fire, broken in pieces, and the fragments ground to a fine dust. He threw the shiny powder into the stream that watered the camp, and made them drink the water as a curse. So assured was his righteous anger, that men and women in their thousands obeyed him.

How Could They Do It?

What was the explanation for this dreadful lapse on the part of the people of God, only a few weeks after they had solemnly vowed they would only ever worship the Lord their God? If you consider the facts, it was not so surprising as it seems. When Moses disappeared into the lofty heights, nobody knew exactly when he was coming back. For a week or two Iife would continue normally, and Aaron kept the great company of people peaceable and quiet. Perhaps when a fortnight had elapsed and there was no sign of his brother, he began to get worried. The leaders of the tribes hung around his door, waiting for news, concerned at this delay in their journey onwards to the land of promise. When they asked how long Moses was going to be, he had to admit he did not know. After three weeks, he perhaps felt angry with Moses for leaving him with all the responsibility and no information about his plans. By five weeks the Israelites were decidedly restive. Rumours were circulating that Moses was dead, victim to some terrible accident on the mountain slopes, or perhaps consumed by the fire that still burnt on the mountaintop. Moses had clearly told the elders of the people before he went up with Joshua ‘Wait here for us until we return to you’ (Exodus 24: 14). But he had failed to return.

There is nothing more dangerous to faith than excessive delay. Perilously weak without his single-minded, dynamic brother, Aaron had his back to the wall. ‘When the people saw that Moses delayed to come down from the mountain, the people gathered themselves together to Aaron’ (Exodus 32:1). His heart sank as he faced the sea of hostile faces. ‘Up,’ they shouted, ‘make us gods who shall go before us.’ He should have stilled them, insisted that they wait longer, and stamped out their treachery to the gracious God who had brought them out of Egypt. But he lacked the courage. Limply he told them to gather together hundreds of gold earrings. Skilled craftsmen prepared the mould, melted them down, and cast the shape of a calf. The molten gold was allowed to cool and worked over with a graving tool. Aaron proclaimed ‘Tomorrow shall be a feast to the Lord’ (v. 5)—it seems he wanted a compromise, he was still telling himself that they were honouring God. But that was not how they saw it. So it was that on the very day Moses came back, the feast was in full progress. And Moses, disgusted to see that the people had broken their covenant with God, destroyed the tablets which recorded the details that confirmed it.

An Urgent Warning

The golden calf incident shows us an urgent warning. Bible students have always expected that Jesus Christ will come back to the earth. There are hundreds of passages in the Old and New Testaments requiring that he will, and many wonderful prophecies have now been fulfilled, so that his coming seems long overdue. This situation is very Iike that of Moses, away on the mount. Jesus has gone up into the clouds to be with God, and commanded his followers to wait for his return (Acts 1:6–11). There is a very real danger that they will begin to wonder what has happened to him, and perhaps to sit back and decide that God’s plan has gone wrong. Jesus frequently warned his disciples how easily this could happen. ‘Therefore, stay awake, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming. But know this, that if the master of the house had known in what part of the night the thief was coming, he would have stayed awake and would not have let his house be broken into. Therefore you also must be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an hour you do not expect’ (Matthew 24:42–44).

Even more pointedly, in his last message to his disciples, the book of Revelation, he seems to draw attention specifically to the tragedy of the golden calf. In a Iist of signs that will lead up to the great battle of Armageddon, he inserts in brackets a warning note. ‘Behold, I am coming Iike a thief. Blessed is the one who stays awake, keeping his garments on, that he may not go about naked and be seen exposed!’ (Revelation 16:15). Moses caught the people stripped and dancing around the golden calf, as he descended from the clouds. In the same way Jesus will find out his people, if they have ceased to expect him. The Apostle Peter explains the reason for Christ’s extended absence. ‘The Lord is not slow to fulfil his promise as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance’ (2 Peter 3:9). Once Christ has come, it will be too late to repent. Every extra day gives us opportunity to prepare for the Kingdom he will bring. ‘Be diligent to be found of him without spot or blemish, and at peace,’ Peter concludes, ‘and count the patience of our Lord as salvation’ (verses 14–15).

The Intercessor

We cannot leave the golden calf episode without noting the reaction of both Moses and God to the people’s descent into idolatry. Moses could justifiably have been insulted at the derogatory way they had spoken of him. ‘As for this Moses’, they had said, ‘the man who brought us up out of the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him’ (Exodus 32:1). After all he was doing for them! Yet when God was angry with the people, Moses instantly sought to intervene. He climbed back up the mountain and prayed to the Lord. ‘Alas, this people has sinned a great sin. They have made for themselves gods of gold. But now, if you will forgive their sin—but if not, please blot me out of your book that you have written’ (vs. 31–32).

God Iistened to his plea. The people would not be cut off. He would punish them, but His plan and the promise He made to Abraham 400 years before would continue. It was only the first of many times that God would demonstrate His patience and forgiveness, and Moses his humility and his love for his people.

Moses the great mediator was the forerunner of Jesus, the supreme high priest and intercessor for all sinners before God. ‘If any man sin,’ wrote John, ‘we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous’ (l John 2:1). Jesus is alive today at God’s right hand, to speak up for his people Iike Moses when they deserve God’s wrath. And God is stilI ready to forgive.

But Moses’ concern for the fate of those who had insulted him is also the example for all people of God. Their duty is not to answer an insult with a blow, or to stop speaking to someone, or go off in a huff, but in love to forgive and forget. ‘I say to you who hear,’ commanded Jesus, ‘love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you’ (Luke 6:27–28). Such grace is a hallmark of the children of God.

David M Pearce