SINCE THEIR EXPULSION from the land of Israel by the Romans, the Jewish people have wandered the world in exile for nearly 2000 years. They spoke the language of every place where they settled. Their ancient language Hebrew was kept alive in their Bible (what we know as the Old Testament), and in religious literature. Its use was reserved for special occasions, prayers, religious study and blessings, and for literary and official purposes.

During the 19th Century a version of pidgin Hebrew was in use in the markets of Jerusalem—it was developed by the Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews in order to understand each other, but it was not a proper language. Hebrew had long since ceased to be the language of the common Jew.

Zionism

In the late 19th Century, galvanised by increasing anti-semitism throughout Europe, the Jewish visionary Theodor Herzl promoted the idea of the Jews returning to Palestine to establish a state of their own. The movement which he spear- headed became known as Zionism, and led eventually to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948.

What would be the official language of this new state? Not Hebrew: Herzl saw the revival of Hebrew as not only impossible, but impracticable. A language that had stopped developing 2000 years ago was not compatible with the modern world. He suggested that they should speak German, the language of modernisation.

But other Zionists disagreed. How can a nation be considered a nation if it doesn’t have its own language? One of these was Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a Russian–Jewish journalist. He and an energetic group of followers made it their goal to revive the ancient language of the Jewish people, and make it the everyday language of the new state for which they were striving.

They encountered resistance from all sides—ultra-Orthodox Jews said Hebrew was a holy language and should be reserved for holy purposes only; secular Jews said there was no need to speak an out-dated language; many simply doubted that it was possible.

The Language Reborn

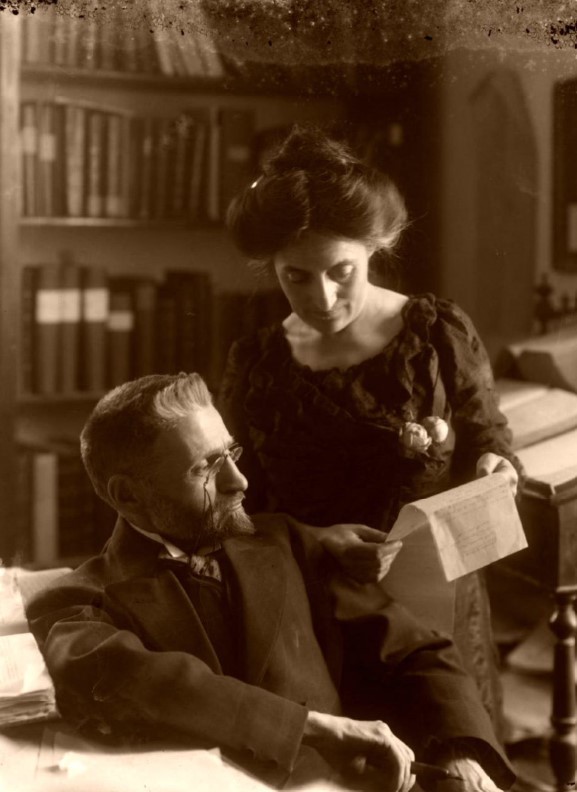

On 13th October 1881, in Paris, Ben Yehuda and some friends held what is believed to be the first modern conversation in Hebrew. Soon afterwards he relocated to Jerusalem. He determined that his family would only speak Hebrew, raising his son Itamar Ben-Avi to be the first native speaker of Modern Hebrew, and attempting to convince other families to do likewise. He founded associations for speaking Hebrew, and published a Hebrew newspaper, HaZvi. Hebrew schools were established in Jewish settlements in Palestine, and for a while Ben Yehuda worked as a teacher. He also compiled a dictionary of modern Hebrew.

At first progress was slow. In 1902, over two decades after their arrival in Jerusalem, Ben Yehuda’s wife recorded that she baked a cake for the tenth family to agree to speak only Hebrew. But during the next two decades the movement grew exponentially. In 1921 the British, who administered the mandate for Palestine, recognised Hebrew as one of the country’s three official languages, along with Arabic and English. Ben Yehuda died in 1922.

Hebrew is now accepted as Israel’s national language. The process of its return to regular usage is unique and could hardly have been foreseen: a sacred language which was effectively dead, without any native speakers, becoming the first language of a nation.

Imaginative Words

During the process of modernisation, old Hebrew words sometimes took on different meanings altogether.

The return of the Jews to their ancestral land was a fulfilment of many Bible prophecies (for example Jeremiah 31:8–10). But the nation of Israel is still self-confident and largely godless, and so it will be until they are finally confronted by their Messiah (Zechariah 12:10).

The prophet Zephaniah looks forward, beyond this present time of trouble, to the Kingdom of God which Jesus Christ will establish on his return. It will be a time of peace and blessing for all nations. And it very much seems as though the project of reviving the ancient Bible language which Ben Yehuda and his associates began with such enthusiasm, will be brought to a fruition which even they did not imagine: ‘At that time I will change the speech of the peoples to a pure speech, that all of them may call upon the name of the Lord and serve him with one accord’ (Zephaniah 3:9).

Tom Ingham